Locating Bridgeton’s Black Brickmaker

- Dr. James Johnson

- Aug 6, 2025

- 2 min read

Updated: Aug 24, 2025

Before his death from dysentery at Morris Island, South Carolina on December 10, 1863,

Ezekiel Barcus eked out a living making bricks in Bridgeton, possibly along East Commerce

Avenue. Identifying locations where some historical actors tread can be a difficult process once

physical traces of their presence have disappeared. In this case, Barcus’s brickyard. However,

history sometimes offers an alternative lens into the past, albeit through a blatantly racist

newspaper entry of the type so prevalent in pre-Civil War and post-Civil War print media.

In the former era, for example, the Bridgeton Pioneer newspaper published a patently racist

advertisement of Black brickmaker Ezekiel Barcus’s business operation on January 28, 1860.

Purportedly submitted by Barcus, the 780-word caricature was accompanied by a curious

attestment certifying the validity of its information (Fig. 2).

The authenticator’s final comment, that the Bridgeton Pioneer “complied with the letter” is

interesting given that Barcus, as well as his wife and oldest child, could not read or write

according to the 1860 federal census (Fig. 3). Nonetheless, if we assume that the Bridgeton

Pioneer received a submission either diectly from or on behalf of Ezekiel Barcus, it would have

been his dictation to a biographer seeking to mock the socio-economic aspirations of Black

Americans. Despite these mean-spirited objectives, complete with liberal use of the N-word,

readers can distinguish an historical overview of Ezikiel Barcus’s twenty-year path to his

brickmaking business.

Following childhood enslavement, presumably in Delaware, Barcus spent twenty years as an

brickmaker’s “prentis” along the Maurice River, Glassboro, Mullica Hill, Woodstown, Salem, and

Bridgeton. In 1859, equating debt with enslavement, Barcus secured help from white men of

means. (Fig. 4, 5). He may have borrowed up to $1500 (Fig. 5).

Despite ethical drawbacks, the published boilerplate for the Barcus enterprise provides

clues to its physical location. We see the “Cumberland Brick Yard” of “E. Barcus & Co.”

was situated “below Elmer’s Mill, on the ground of Levi Dear [sic], in Bridgeton. N.J.

(Fig. 6).” When Elmer’s son Charles died in 1901, his obituary confirmed the mill’s

location (Fig.7).

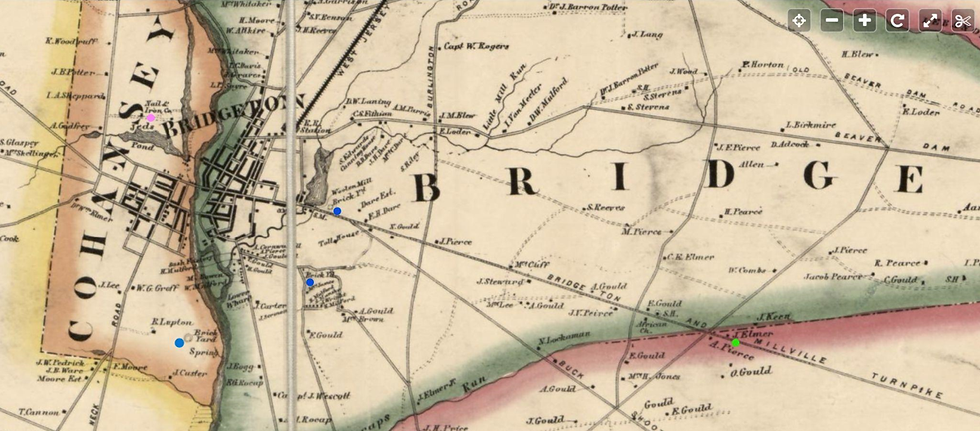

On the following 1862 map of Bridgeton Township, J. Elmer’s Mill is indicated by the green dot

along Millville Pike (East Commerce street). Three brickyards are indicated by blue dots. My

tentative speculation is that Barcus’s brickyard sits at the upper-most of the 3 blue dots (Fig. 7).

A brief search of county tax records has not shown any documents associated with Ezekiel

Barcus. Perhaps a deeper dive into similar databases will prove fruitful. I look forward to

responses.

By Dr. James Elton Johnson

Comments